WHAT IS A VETERAN? - A “Veteran” whether active duty, discharged, retired, or reserve is someone who, at one point in his life, wrote a blank check made payable to the United States of America, for an amount of up to, and including his life. That is HONOR! And there are too many people in this country today who no longer understand that fact. Air Force Veteran and Turnbow-Higgs American Legion Post 240 twenty-year member, Dean Jones, is such a person. Dean wrote his blank check, made payable to the United States of America, in 1963.

Currently (2023) a resident of Stephenville, Texas, Dean began his high school senior year at Dublin High School in 1960, transferring to Waco High School in spring of 1961. Upon his Waco High School Graduation, he enrolled at The University of Houston and a year later transferred to Tarleton State University.

He entered the summer of 1963 having earned 61collegiate semester hours with a growing boredom and lack of interest in academic lifestyle and began re-evaluating his life choices. Heeding the advice of his older brother, an Air Force Veteran, Dean researched and considered the many excellent Air Force career possibilities and learned his sixty-one collegiate semester hours qualified him for the Air Force Aviation Cadet program.

As summer of 1963 ended, and following weeks of consideration, Dean chose the Air Force Aviation Cadet Program and traveled to Waco for pre-acceptance testing. Shortly thereafter, he learned of his acceptance into the program, but no class date had been set. Rather than wait for a class assignment, Dean decided to proceed with enlistment and complete basic training at Lackland AFB in San Antonio.

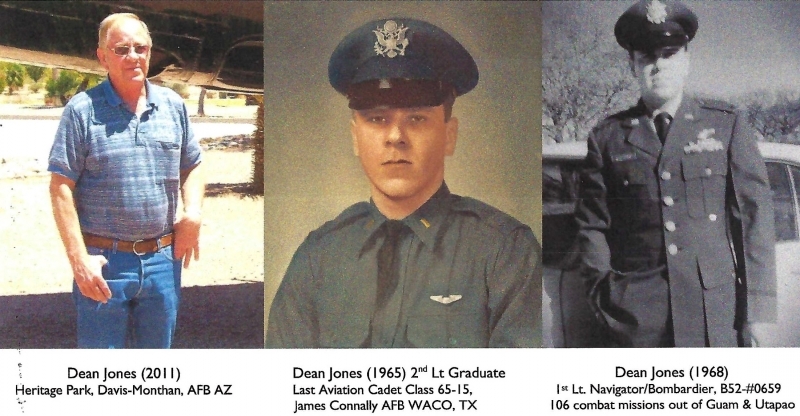

From Basic Airman to Captain with excerpts and photos from various sources, Dean recounts his exploits as a young cadet and eventually a B-52 Navigator Bombardier, and recipient of the following Military Medals & Ribbons- Air Medal, with 4 Oak Leaf clusters, National Defense Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, Vietnam Campaign Medal, USAF Good Conduct Medal, USAF Longevity Ribbon, USAF Small Arms Expert Ribbon and Outstanding Unit Ribbon.

BASIC TRAINING ENLISTMENT- Dean Jones- My Story.

Dad gave me a ride to the big city of Hamilton, Texas where I met my Air Force recruiter who ferried me sixty miles to James Connally Air Force Base hospital in Waco, Texas for pre-enlistment physical. It was there that I first experienced the military's MO of "hurry up and wait". The ordeal took all day.

Having successfully completed medical exams and taking the military service oath to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States…and bear true faith and allegiance to the same” we boarded a bus for the ninety-mile trip to Dallas where we joined other recruits from the Dallas area.

We continued our journey to Air force Basic Training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio via Trans Texas Airlines, affectionately known as Tree Top Airlines. The 270-mile flight was my first airplane ride. Our flight encountered thunderstorms resulting in turbulence that caused some passengers to suffer from motion sickness. Fortunately, the turbulence did not affect me, but it was a forebearer of things to come during my time as a cadet. Our flight landed at Kelly AFB, where we boarded a bus, and continued our journey to Lackland AFB, and Basic Training.

Upon completion of Basic Training in November of 1963, I was issued my Airman 3rd class stripe, a monthly paycheck for $80, and placed on Graduate status at Lackland AFB, waiting on a Cadet Class date. Graduate status was an in-limbo condition for Airmen who were waiting on a tech school assignment, OCS, or discharge. I was the Dorm Chief during Basic training and became the Graduate-in-Charge until departure for Cadet Class. Rank and privilege enabled me to maneuver my way out of KP and other similar clean-up duties.

Like most people I will never forget where I was and what I was doing the day President Kennedy was assassinated in November of 1963. My Assistant Graduate-in-Charge, our First Sgt and I, had finished lunch and returned to the barracks where we were playing hearts when suddenly the radio broadcast the news about the shooting. The card game and most all planned activities ceased, and like most Americans, for the next few days, we sat shocked listening/watching the radio/TV reports of the tragic event.

On a lighter note, the January 1, 1964, Cotton Bowl game between Texas and Navy, led by Heisman Trophy winner Roger Staubach, proved to be a very profitable day for me. Navy was a big favorite of most guys from the northeast. Being a Texas native, I bet what an A/3C could afford on the Texas Longhorns. They had Staubach’s number on this day, winning 28-7.

THE LAST AVIATION CADET NAVIGATOR CLASS 65-15 (WIKIPEDIA)

The last Aviation Cadet navigator class was 65–15 at James Connally AFB. Was made up of Eulalio Arzaga, Jr., James J. Crowling, Jr., Ronald M. Durgee, Harry W. Elliott, Timothy J. Geary, Robert E. Girvan, Glen D. Green, Paul J. Gringot, Jr., William P. Hagopian, Steven V. Harper, Robert D. Humphrey, Hollis D. Jones, Evert F. Larson, Gerald J. Lawrence, Thomas J. Mitchell, Ronald W. Oberender, Raymond E. Powell, Victor B. Putz, Milton Spivack, Donald E. Templeman, and Herbert F. Turney. These aviation cadets became USAF 2nd lieutenants and were awarded their navigator wings on 3 March 1965. Class 65-15 chose classmate Cadet Steven V. Harper of Miami, Florida, for the honor of "Last Aviation Cadet" based on his high academic, military, and flying grades.

My Aviation Cadet Navigator Training class assignment finally occurred in March of 1964. I departed Lackland AFB and arrived at JCAFB (John Connally AFB) in Waco, Texas as a future member of Aviation Cadets, Class 65-15, the last class of Aviation Cadets.

Being in the last class did not alter the usual rigors of military and navigator training, and traditional harassment by upper classmen. Since we were in the last class, some of us were disappointed that harassment of under classmen would end with our class.

Our flight training began during the early sweltering summer days of 1964. The hot Texas summer temperatures created thermal air turbulence causing the old trustworthy T-29 to invariably start bouncing around and my stomach bounced right along with it as we descended into John Connally AFB. I was seriously thinking about junking the flying idea until after a few missions an instructor finally gave me a few hints such as look out the window, eat crackers, etc. My queasy stomach got better, and I stayed with the program and finished second in our class.

I celebrated my 21st birthday flying night grid over Las Vegas, New Mexico. Navigationally speaking, the night grid was such a panic that it did not dawn on me that my 21st birthday had arrived until we were nearing landing strip in Waco.

We graduated in March 1965, and of the forty cadets who started, twenty-one finished. General Benjamin Foulois, one the original founders of the Army Air Corps before WWI, spoke at our graduation. After completing Navigator Training, I was considering making the Air Force a career. So, I decided to go to Navigator Bombardier Training. I had the impression that SAC radar/navigators were extremely important to the mission and spot promotions were great. To my chagrin, shortly after I went operational, spot promotions were discontinued. Poor timing on my part!

NAVIGATOR BOMBARDIER TRAINING (NBT) At MATHER AFB

In April of 1965, four other classmates and I started Navigator Bombardier Training (NBT) at Mather AFB in Sacramento. We trained in both the ASQ-38 and 48 bomb systems at Mather and upon completion were sent TDY (Temporary Duty) to Survival School at Stead AFB in Reno, and to Combat Crew Training at Castle AFB in Merced, Ca.

MY FIRST OPERATIONAL ASSIGNMENT

In March of 1966, two and a half years following my enlistment date, I finally arrived at Bergstrom AFB to begin my first operational assignment.

I was given a choice between Bergstrom AFB near Austin, Texas, or SAC Bases such as, Glasgow, MT, or Minot North Dakota, I chose Bergstrom AFB. My preference for hot Texas summers with older planes and bomb systems prevailed over the subzero winter weather in Glasgow, MT and Minot, ND. I decided on Bergstrom AFB in Austin even though the 486th Bomb Squadron had the older D model planes.

Arriving at Bergstrom, I learned that the 486th Bomb Squadron was short on navigators. So, after getting somewhat settled and ready for my second training mission, the powers that be decided due to the shortage, that I (not yet checked out) would be the navigator on the next "chrome dome" sortie which, for the unfamiliar, was a 24-hour mission over northern Canada and Greenland with live nuclear weapons on board. It was the heart of the airborne alert system in use during the "Cold War".

The next morning as we were taxiing out for the "chrome dome" mission we were stopped by the landing of another airplane. The incoming airplane just happened to be carrying Operational Readiness Inspection (ORI) personnel. As you might imagine, paperwork was rapidly completed regarding an update on my operational status.

As far as the ORI went, the mission consisted of a new low-level route with new targets. The 486th along with other squadrons flunked it. We passed the rerun though and my "chrome dome" mission happened later. In fact, I went on a few of those before our squadron was relieved of airborne alert duty in favor of iron bomb training where the drop site was off the Texas coast on Matagorda Island. My well thought out decision to pick Bergstrom AFB did not last very long. Vietnam was beginning to heat up and our 486th was moved to March AFB in Riverside, California. and joined the 22nd Bomb Wing in October of 1966.

Strange how you remember dates by events that occur at the time, but I recall routing my move to Riverside by using the northern trail. I spent my first night in Denver, the second in Salt Lake City, and then on to Reno and Sacramento. While driving across the expansive nothingness of north central Nevada, I managed to tune in to the Major League Baseball World Series between the Baltimore Orioles and the Los Angeles Dodgers on the radio. Being a New York Yankee fan, I was delighted when Baltimore swept the series in four games sending the long-time hated Yankee nemesis, Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers, home without a win.

By the spring of 1967 I had become adapted to Southern California and had decided that it was much different than Sacramento or San Francisco. Since I was single, I did what bachelors tend to do and developed a couple of female relationships in Riverside and San Bernadino. However, my social life went downhill when in April 1967 the 486th Bomb Squadron received orders for a 6-month TDY tour in SE Asia. Our "tour" began in Guam. Some of our B-52D model planes based at March AFB were flown to Guam to be eventually put in service there.

My first trip to SE Asia was interesting in that my crew and another crew were assigned to fly two of the iron-bomb converted B-52s based at March AFB to Guam. Our flight plan took us up to San Francisco and then out past the Farillon Islands for a couple of hours to meet tankers and be refueled. We took off in the morning and the flight followed the sun for about 15 hours. After refueling, our route across the Pacific went approximately two hundred miles south of the Hawaiian Islands, then directly over Wake Island and on to Guam.

MID PACIFIC OCEAN NAVIGATOR’S CHALLENGE- After refueling, the plot thickens.

About an hour after disconnecting from tankers, there was a pleasant but short conversation between the two pilots. It ended with the words "I thought you guys had the lead."

At that point I looked at my RN and he looked at me and we both said 'uh, oh' at the same time. I don't remember if we and the other crew ever determined how, who, or what got screwed up, but we took the lead out in the middle of the Pacific, and I sure did hope that my flight plan and the forecast winds were holding form.

For the unfamiliar, during the cold war, navigational aids were assumed to be inoperative per SAC so, the only navigational equipment on board a B-52 was the most modern bombing/navigational radar available plus doppler radar, the pilot's Tacan, a sextant, and a drift meter.

As I mentioned, it was daytime, so the sun was the only celestial aid. I immediately started calculating info for a sun shot and the EWO (Electronic Warfare Officer) installed our sextant. EWOs usually took celestial shots since they were also navigators and had celestial training and were in the upper crew compartment.

That day on our west/southwest heading the sun was not of the greatest value because it was mostly diagonal rather than a course or speed line. Anyway, the EWO took a couple of shots over a period of about 20 minutes, and I put that together along with what I hoped was halfway dependable doppler information and DR (Dead Reckoning) from our flight plan and plotted what I thought was a decent fix.

I got on the intercom and told the pilot to take 1 degree left. He said "What? Is that all?" and I said yes and then we both had a tentative chuckle. He turned 1 degree.

A couple of hours or so later I thought I could occasionally make out a glimpse of a small radar return a little over two hundred miles off to our north. I was certainly hoping big time that the return was the southern most island in the Hawaiian chain since we were out in the middle of the Pacific at 35,000 ft without any ground or air contact for hours.

Based on that radar return, more sun shots, and doppler winds I asked my pilot to take another degree left. He made some random comments which I ignored and turned another degree. As all navigators learn in early training, a degree or two turn from 1,500 miles away can mean hitting or missing your target by a lot of miles. Two to three hours later, I saw a small blip beginning to appear on the radar and the 'hard to believe' was about to occur. We passed almost directly over Wake Island and within 2 minutes of my ETA. What a relief!

My EWO said something to the effect of "pulling one out of your butt.". I took immediate offense to that remark and jokingly, told him, “I had it all the way and thanks for the sun shots.” The rest of the way into Guam was no sweat.

THE GUAM BOMB

Those who were in Guam during the mid to late sixties might remember the "Guam bomb". It was a dilapidated black 1957, 4 door Plymouth with push button drive and a partially rusted out floorboard. A good friend of mine from NBT (navigator bomb school) had been there 6 months TDY and his squadron was about to return to their home base of McCoy in Orlando. His crew happened to own this rare vehicle and they made my pilot, EWO, and I an offer we could not refuse. We acquired the Guam Bomb for $300 cash. The car still ran well. The biggest problem was during rainstorms, which are frequent there, water splashed up on your feet through the floorboard. We made trial runs (which is why we bought it.) to "enjoy" the amazing sights of Agana, Guam. Funny side of that story is that before we departed, we found another gullible incoming crew who bought it. By that time, the transmission had to be warmed before it would shift into drive. So, before they arrived to make the transaction, my pilot got in the car, put it in reverse and spent about 10 minutes backing it around the parking lot. Transmission was working fine when they got there. I tried to stay out of sight. By the time we made our second TDY trip to Guam, it had met its demise.

THE NARROW ESCAPE- BLOWN TIRE DURING TAKE-OFF- JULY 1,1967

After being in Guam for almost 3 months and becoming accustomed to the routine of flying combat missions at all times of day and night, an event occurred that had a profound effect on mine and my fellow crew members’ lives.

On July 7th, 1967, we were scheduled for a mission takeoff time of 2:00 a.m. We were the last plane in a nine-plane wave. Target study, mission briefing, preflight airplane inspection, pulling pins out of eighty internally carried bombs of the 500-pound variety and visually checking the 24, 750-pounders carried externally went as usual.

Time for these activities was not a problem since crews were to be at briefing 4 hours prior to takeoff.

As 2:00 a.m. approached planes in our wave began taxiing for takeoff and we fell in line as the ninth plane. The weather was okay that night and the copilot was going to manage the takeoff, which was not a big deal. The roll down the runway with 57,000 pounds of bombs and about 3/4ths of a fuel load in a B-52D uses the entire runway.

The Anderson AFB, Guam single runway is laid out on a northeast to southwest vector. Takeoff to the SW is over land and takeoff to the NE is over a 600-foot cliff overlooking the Pacific. That night we were extremely fortunate in that there was a breeze from the north/northeast. Our liftoff speed had been calculated to be 154 knots. Things were quiet as we gained speed.

Not more than 3-seconds after we had reached our "committed" speed, we heard a loud thump. It sounded like we had run over a barrel, or a big tin can. Almost immediately, the pilot came on intercom and in a very high-pitched voice announced, "I've got the airplane. We've had a blowout".

We had passed "committed" speed and were not gaining speed at all. The next few seconds were about as tense as you would ever want to be in an airplane. The ground speed on my panel was showing 135 which was obviously below liftoff speed. The plane was favoring the blown tire and the pilots were trying to keep the airplane in the middle of the runway. As we neared the end of the runway, the radar navigator announced while he was looking through the optics that a front truck was on fire.

As we reached the end of the runway, both pilots were pulling back as much as possible on their control wheels and as we went over the cliff the airplane nose came up rapidly. B-52s do not climb with a nose-up attitude so the pilot quickly began pushing the control wheel down and the nose started to come down while we were rapidly losing altitude. The pilot told the crew to get ready to bail out. That pronouncement is a bit unnerving especially if you are in a downward ejection seat that requires a minimum of 400 ft. altitude for seat separation and chute opening.

Even though the nose had come down, we were still dropping, and the pilot told the copilot to raise the landing gear to help stop our rapid descent. The RN then yelled it was still on fire and the pilot said I have got to raise it. The plane was shaking so much in that short period of time that the RN could not get hold of the emergency bomb release handle on the panel above his head.

Finally, with a burning tire inside the wheel well, the plane leveled 50-100 ft above the water according to our gunner. As we began gaining altitude and air speed, the copilot put the gear down and the RN could tell looking through the optics that the tire fire was extinguished. At about 5,000 ft, I went back to look at the front wheel well to see if there was any visible damage and see if I could tell which tire had blown. I could not see any damage inside the wheel well and the right front truck appeared to be the one with the blown tire although it was hard to tell for sure.

Instead of dropping our bomb load and then burning fuel for hours before landing, the Aircraft Commander decided to continue the mission. We finally caught up with the wave by the time we reached the refueling track over the Philippines. The rest of the mission went as planned until we got back to Guam.

Returning to Guam after a more than tiring eleven plus hour mission, we started our descent from 46 thousand ft. and on our landing pattern penetration, another problem developed. When lowering the gear, the left main aft gear would not come down and lock into position. We broke off the descent at 20,000 ft and continued trying procedures to get the gear down until, for some reason it decided to cooperate, and it came down and locked and we started descent again.

During the flight we continued discussing the blown tire and the aircraft pulling to the right as we were rolling down the runway. When we reached 10,000 ft on our descent, the A/C (Aircraft Commander) decided it would be a good idea for me to take one more look at the front trucks to try to determine for sure which tire had blown. He did not want to raise the gear again because of the earlier problems we had trying to lower it.

So, again I unhooked my parachute from my ejection seat and went back through the aft bulkhead to the front wheel well. Getting through the small passageway with a parachute strapped on is difficult but once I had gotten back into the open wheel well in the daylight it was much easier to tell which tire had blown. With that information, the A/C then knew for sure which truck to retract for landing.

To burn fuel down to minimums and allow ground personnel to visually check for any aircraft damage, we made several "low goes". Of course, all kinds of emergency equipment were aligned along the runway, and most of Andersen AFB commanding officers had gathered nearby to witness the landing.

Once we reached fuel minimums, the RN and I went to the upper deck and strapped in for landing. The landing went okay until we touched down. On first contact one of the aft main tires blew and then two more tires on the other trucks blew as we were going down the runway.

The pilots managed somehow to keep the plane on the runway. After coming to a stop, we were, of course, trying to get off the plane quickly but it was more difficult than usual because the entry/exit hatch (navigator's hatch) would only open about hallway since the plane tilted so much toward the ground with the right truck retracted.

EPILOGUE

After three TDY trips to SE Asia, and 106 combat missions out of Guam and Utapao, I decided that was enough. Things had changed during the fleeting period since I had enlisted. SAC was not so enticing anymore with no spot promotions and after going through two years of specialized training for SAC bombers moving to another Command would not be looked upon favorably.

There were other factors leading to my departure. There were programs for enlisted personnel to return to school for an undergraduate degree, and programs for officers to return to school for a graduate degree. However, there was nothing for an officer to go back for an undergraduate degree. So, I submitted my paperwork and, because I had received a regular commission on graduation from Aviation Cadets, I had to wait a year before being separated from the USAF.

I departed active duty in June of 1969, and immediately joined the reserves at Kelly AFB, San Antonio flying C-124s and enrolling at University of Texas in Austin. Flying B-52s to flying C-124s was quite a change. My first reserve mission was ferrying two helicopters to Vietnam. Took 10 days for the round trip. I think we landed on every rock in the Pacific.

Our ‘Home in the Sky’ B-52D #56-0659 airplane ended up at Davis-Monthan AFB, AZ and was placed along with hundreds of other airplanes in the "bone yard". Through unusual circumstances whereby the extraordinary history of #0659 was discovered, it and 5 or 6 other Vietnam Era aircraft were moved to Heritage Park located at the base entrance in 1991.

In 2011, Bill Bushman and I met in Tucson and toured Heritage Park. A few of the photos taken during our tour of Heritage Park are included within this story. Our beloved ‘Home in The Sky’ B-52D #0659, and plaque displayed by the airplane are most prominent. It is my understanding that a few years ago the park was removed to allow for base expansion and the fuselage section bearing the crew names as well as the tail gunner section of #0659 were sent to Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio. Do not know for certain but I imagine that was the only time crew names were ever painted on a B-52.

Strategic Air Command’s (SAC) strategy always stressed keeping the same crew together to improve functionality, my crew, E-70, stayed together for 3 years, which was much longer than most. Except for the gunner and I, all are deceased (2023).

Bill and I were big sports fans and communicated frequently via telephone, he was from Iowa and the Big Ten Conference, and I was from Texas and my beloved Southwest Conference. Our "sporty" conversations usually became competitive but always ended on a friendly note when we transitioned to politics. We shared the same political mindset and conversations quickly found common ground.

Before his passing in 2015, our Aircraft Commander and pilot Lt. Col. William J. Bushman (retired), authored an extended article regarding that narrow escape on July 1, 1967. The article was published in the book-

WE WERE CREWDOGS VI, CHAPTER 3, EMERGENCY BLOWN TIRE ON TAKEOFF.