The GI Bill

The GI Bill

20th Century America’s Greatest Legislation

The Problem

“Even a convict who is discharged from prison is given some money and a suit of clothes.

The veteran, when he is discharged from a hospital or separation center, is given neither.”

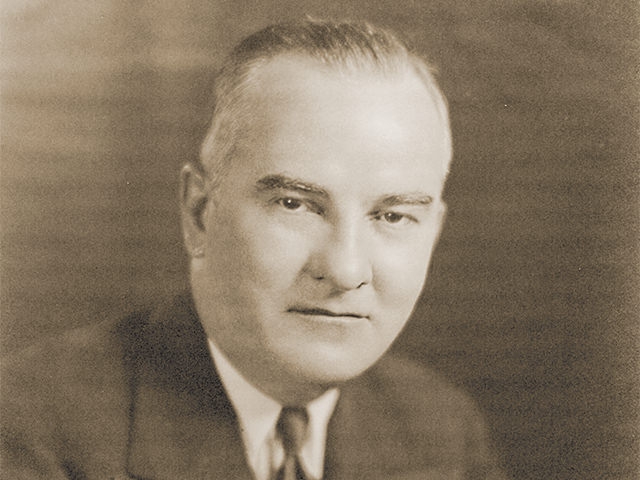

American Legion National Commander Warren Atherton, 1943

By the time of the 25th American Legion National Convention Sept. 21-23, 1943, in Omaha, Neb., more than 600 bills had been introduced to address a wave of medically discharged World War II GIs coming home to virtually no government support network. An estimated 75,000 per month were pouring into communities where VA services were still in their infancy, few programs existed to retrain disabled veterans for new careers and no unemployment pay was offered. Newly elected National Commander Warren Atherton assembled a blue-ribbon American Legion team to draft one omnibus bill to assist all veterans, disabled or not, in the return to civilian life.

The Case Studies

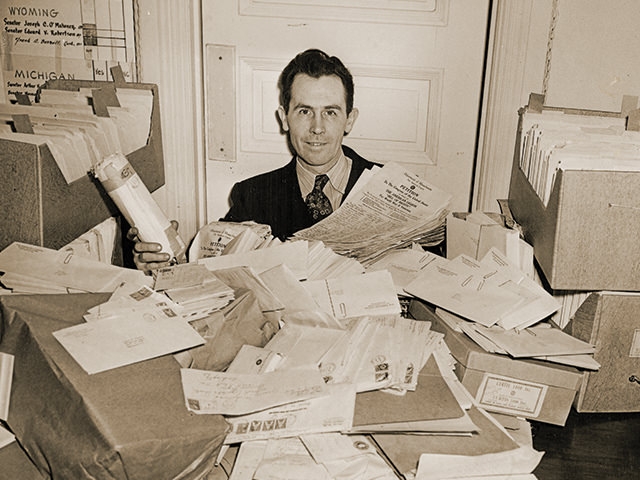

The American Legion was determined to put a human face on the problem. On Nov. 26, 1943, National Commander Atherton sent a telegram to all of the organization’s service officers nationwide. He called for case studies to make the point that these GIs were coming home to little or no support. Within 24 hours, he received 1,536 testimonials. On Nov. 29, Atherton appeared before Congress, accompanied by some of the disabled veterans, and began reading their off their case studies. They seemed to be from every congressional district in America.

The Bill

Former Illinois Gov. John Stelle, who would go on to serve as national commander of The American Legion in 1945 and 1946, was appointed to lead the committee to distill all of The American Legion’s preferred benefits – including free college tuition, vocational training and $20 a week in unemployment pay for a maximum of 52 weeks – into one set of 10 provisions in a comprehensive bill. Past National Commander Harry W. Colmery of Kansas, in December of 1943, drafted the legislation by hand in a room of the Mayflower Hotel. Several modifications would be made before it reached Congress, but the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 did not deviate from its 10 key provisions: college education, vocational training, readjustment pay, home and business loans, discharge review, adequate hospitalization, prompt settlement of disability claims, mustering-out pay, employment services and concentration of all these provisions under the Veterans Administration.

The Campaign

Hearst Newspapers led a national campaign in support of the GI Bill. Criticism arose over the 52-20 compensation, some suggesting that such a benefit would turn veterans into slackers and that African-American veterans should not receive the same benefit as those who were white. The Army and the Navy both opposed the discharge-review feature of the bill, which would suddenly give veterans the route to appeal conditions of discharge, if less than honorable. The American Legion fought off the critics, including some other veterans service organizations that publicly opposed it on the concern that money spent educating able-bodied veterans was money that would be lost providing care for those who were disabled.

Passage

On March 17, 1944, the measure unanimously passed in the Senate, but the House remained stalled over the 52-20 provision. Backed by a nationwide petition drive and Hearst’s editorial support, the House finally passed on the legislation on May 18, 1944. A conference committee was assembled to marry up the Senate and House versions. The House conferees were deadlocked 3-3 with the tiebreaking vote, that of Rep. John Gibson, in rural Georgia, recovering from an illness. After a week of deliberations, the GI Bill remained paralyzed. On the evening of June 9, the committee agreed to have one more meeting the following day, and if it could not break the impasse, the bill would die there.

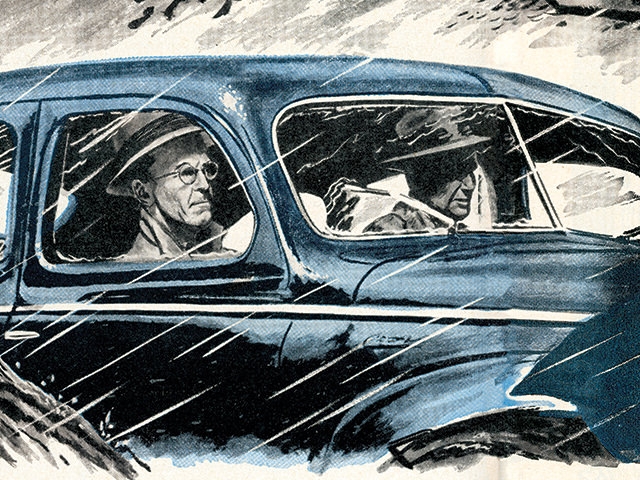

A Wild Ride from Georgia

The Legion gets through to an operator in Atlanta who calls Gibson’s home every five minutes until he answers at 11 p.m. The Legion, assisted by military and police escorts, take Gibson on 90-mile high-speed trip through a rainstorm to the Jacksonville, Fla., airport where he is flown to Washington, arriving shortly after 6 a.m. He casts the vote to send the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 to the president’s desk and promises to make public the name of anyone who would vote against it, along with their reasons. The conference committee tie suddenly became unanimous in favor.

The Effects

College enrollment nationwide ballooned from 1.6 million to 2.1 million between 1945 and 1946. By 1947, half of America’s college students were military veterans using their GI Bill benefits. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 would ultimately send approximately 8 million World War II veterans to college and vocational training programs. About 30 percent of World War II veterans used their GI Bill benefits to buy homes, farms and businesses. Only 14 percent took full advantage of their one-year unemployment compensation, the 52-20 provision that critics argued would be exploited by the veterans. The estimated return on federal investment was $7 for every dollar allocated to veterans through the GI Bill.

Subsequent Versions

The GI Bill would be reintroduced and passed for subsequent war eras, each time a little more watered down that the previous version. The 52-20 provision, for instance, became $26 a week for 20 weeks in unemployment compensation for Korean War veterans, whose college funds were no longer paid to the institutions according to their tuition costs but were held to a $110 per month stipend. Stipends paid to Vietnam War GI Bill users did not cover the cost of college until the mid-1960s. The stipends were reduced to $100 per month in 1966 when the benefits were extended to veterans who had not served during wartime. The American Legion persistently fought for higher stipends and by 1977, the amount had climbed to $311 per month.

The Montgomery GI Bill

The Montgomery GI Bill and other post-service federal readjustment programs for veterans had grown complicated. The benefits could be found in six different chapters of U.S. Code. Moreover, the benefits had not kept up with soaring college tuitions and living expenses, nor with changes in the way 21st century students receive higher educations. A change was needed.

The Post 9/11 GI Bill

“The GI Bill of Rights was the law that worked, the law that paid for itself and reaped dividends because it made the American dream come true for so many. They had to make the dream work for themselves, and if for some reason, it didn’t, they had no grounds for complaints.”

Author Michael Bennett, “When Dreams Came True: The GI Bill and the Making of Modern America”

On his first day in the U.S. Senate in January 2007, Vietnam War veteran and American Legion member James Webb of Virginia introduced legislation to significantly reboot the GI Bill. The Post 9/11 Veterans Educational Assistance Act would more effectively tie the benefit with the actual cost of higher education. College tuitions would again be paid directly to the institutions. Stipends for books and other expenses would be paid to the veterans. The benefit would also be transferable to dependents of qualified veterans, and the new GI Bill would add five years to the eligibility window, from 10 years to 15. In 2017, the Harry W. Colmery Veterans Educational Assistance Act was passed (named for the American Legion National Commander who wrote the original measure in pencil) to lift the 15-year restriction. It would be called the “Forever GI Bill.”