Victor Pividori stepped onto French soil on D-Day plus six after waiting for days on a ship in the English Channel. He would spend his time in the European theater of World War II helping to establish communications, mostly between the front lines and command in the rear.

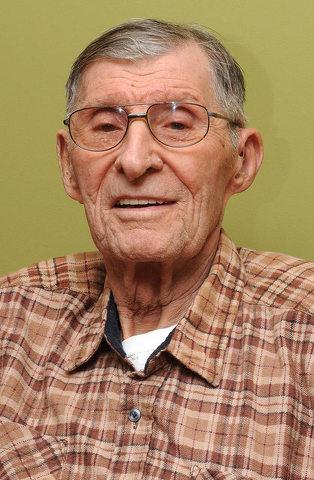

The 94-year-old Homer City resident recently recalled his time in the service while talking to Jeff Knight, his co-worker and friend since 1961, and The Indiana Gazette.

Pividori was part of the 3rd Army, 8th Corps, 59th Signal Battalion, and served in Company B. He remembers stepping off the landing craft onto Omaha Beach and wading ashore as the tide was rolling out.

He was part of an unceasing stream of personnel and gear that came ashore after the Allies poked a hole in Hitler’s Atlantic Wall.

Though Pividori was not in the midst of the intense action on the first days of the beach landings, he was relatively close to the front of the queue: 1 million tons of supplies, 100,000 vehicles and 600,000 personnel came ashore in the Omaha Beach zone over 100 days, according to the Army Corps of Engineers.

The landings, codenamed Operation Neptune, were part of the largest sea invasion in history — and it was Pividori’s job to help troops talk to each other once they were ashore.

“My job started the minute I hit the ground,” he said.

He remembers the beach being chaotic and that there wasn’t much room to move around.

Just south of the landing sites, Pividori said he saw a U.S. paratrooper hanging dead from a tree. This would be the first of the casualties of war, both American and German, the young soldier would see on the march to Berlin.

Before Pividori set foot on French soil to help liberate Europe from Nazi Germany’s grasp, he trained at Indian Town Gap, then Fort Jackson and on to Tennessee for maneuvers.

He entered the service on April 22, 1943, at 20 years old. His family lived in Kent at the time. His service record, according to current archives, lists his occupation before joining the Army as a farmhand.

“Looking back on my service time, I can see how the Army taught me how to make do for yourself if you got into trouble,” he said.

“The officers I served under were good men, they always treated everyone the same. I was a sergeant with a six-man squad and I treated them all the same.”

He remembers telling a sergeant during training that he couldn’t swim. That sergeant promptly tossed him into 9 feet of water and told him what to do. Eventually, Pividori was able to run wire while swimming across a river.

After training, it was on to New Jersey, where he and other personnel boarded troop transports bound for Britain.

Such is the story of how a young man from western Pennsylvania came to be unspooling wire from the back of a Jeep at 30 mph across Western Europe, linking the front lines with command posts and headquarters. He remembered one driver in particular, Peters, as the best.

“When the fire was flying, he was going, buddy,” said Pividori.Sometimes Pividori would have to string the wire up into the trees so it wouldn’t be as easily detected and could be somewhat protected from damage. It was during one of these times that he had a close call with a German sniper who fired at him.

“You never saw them,” he said. “You had to know what to look for.”

By that time, though, Pividori had lost much of his fear. He said he was scared when he came ashore in Normandy but later didn’t worry as much about getting shot.

“If you (were to) think about it, you would be in a hell of a mess,” he said.

There wasn’t much sleep to be had for the signal guys, he said. Shelling and sabotage would frequently sever communications. If this happened, he would get a call on his phone then “tap the line” to determine if the break was from his position — back from the front — or closer to the fighting. He said once he found the break he could splice it and have it transmitting again in less than five minutes.

Pividori also had to be evasive with the Germans. While on his telephone, he would often be directed to go in certain compass directions to find the right position, rather than give his specific location so he or the wire could not be found.

He kept a carbine, a light automatic rifle, in the Jeep, and always carried a sidearm, but Pividori said he never had to use them in his support role.

“We weren’t there to kill but to keep communications open.”

Still, he was exposed to the ravages of warfare. When they landed in France, he saw his first dead German soldier in one of the hedgerows that dotted the landscape. He remembers the widespread destruction, specifically all of the destroyed bridges throughout France.

From June to December, Pividori and his unit strung and repaired wire through freshly retaken French and Belgian territory.

Then, Pividori came to Bastogne. The Belgian town just miles from Luxembourg was a part of the infamous Battle of the Bulge, the common name for the last German offensive of the war due to the “bulge” in the lines. The Reich committed hundreds of thousands of men and thousands of pieces of hardware for a last-ditch effort to break through the Allies’ western advance. It was the bloodiest battle of the war for the U.S. with about 8,500 killed and about 90,000 total casualties.

The period from Dec. 16 to Jan. 25 in the Ardennes is known by its survivors for its brutal combat conditions: bitter cold with no fires permitted for many troops, meaning no hot food; inadequate winter clothing for some; poor military intelligence; bad weather that prevented air resupply and fire support; and incessant artillery shelling.

Pividori remembers it being so cold that mines wouldn’t even detonate when tanks rolled over them. One of his most vivid memories is jumping into a foxhole, grabbing a hot cup of coffee and burning his lips. He and his men often slept right in the snow and ice, sometimes in buildings if they could find them.

But overall, he described the push from Normandy to Berlin as “all the same,” no high points. There were a couple of opportunities to relax after landing in France, but not much, and it wasn’t good rest, he said.

It was in Berlin that he saw Gen. George S. Patton, who commanded the 3rd Army during the campaign. He also got a glimpse of Russian soldiers in Berlin, where Allied troops came together after rolling back years of German territorial gains.

He said he and his men didn’t make a big deal of it on hearing of Hitler’s death. For them there were still tasks to complete and a war to finish.

“When the Army tells you to do something, buddy, you better do it,” he said.

After the German surrender, Pividori drove his men back to the seashore in France to return to England, but they didn’t have enough points to go back right away. Instead, they went to Paris, where Pividori said he had some good times and got to see the sights. During that trip he saw German civilians on the Autobahn, mothers with their children, and remembers thinking that “they seemed to be good people.” He gave away his rations to the civilians when he could.

Eventually he was able to go home and see his family in December 1945 for the first time since shipping out.

He said when he got home he thought a lot about his buddies. He went to Chicago to work at a mattress factory and during this time traveled to North Carolina, New Jersey and Texas to see his friends from the war.

After his travels, he came back to Indiana. An official from the R&P Coal Co., whom he had worked for before the war, asked him not only to come back at work at the mine, but also join the Indiana American Legion Post 141, where he’s been a member for 62 years.

He married Loretta P. Clement in 1955. They had four children: Victoria, Susan, Bryan and Lisa.

He had four brothers in other WWII campaigns and all of them returned home. John, a medic, was one of the first onto the beach in an invasion in North Africa. Fred was a cannoneer who invaded Italy. Lou was a Navy Seabee and made a career of the military. Alex served in the Pacific.

One of his regrets, he said, was never returning to France with his wife, who passed away in 2000.

View more photo galleries by Post 141 in Indiana, Pennsylvania