There was the right way, the wrong way and the Army way.

In 1950, as a young soldier training to serve in Korea, Hank Shiner was taught that the Army way was the only way that should matter to him.

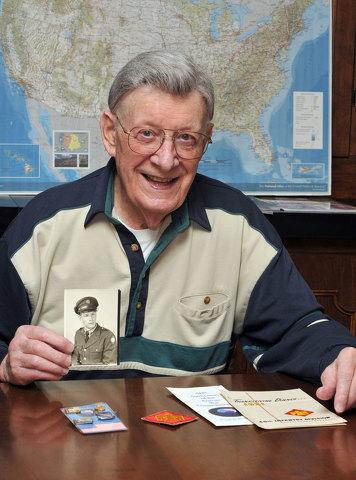

With a sheepish smile crossing his face Shiner, 88, of Indiana, recently admitted it took him a while to learn that lesson.

Twice he “extended” without permission 72-hour leaves he had been granted and twice he was reprimanded and denied privileges for weeks at a time. And that was all before he completed training camp.

But somehow Shiner, then 23, grew up during the two years he served on Army tanks in Korea as a member of the 45th Thunderbird Division of Oklahoma.

“I did something wrong by staying away without getting permission,” Shiner said about his maturation in the military. “I just felt guilty. I wanted to make it all up.”

He eventually asked his captain what he would have to do to change and advance in the Army.

“‘To make tank commander, you will have to become a soldier first,’ I remember him telling me that,” Shiner said.

So he became a soldier, Tank Commander Sgt. 1st Class Henry “Hank” Shiner.

Shiner was born in Ernest but spent summers in Indiana with relatives. He started Indiana High School but left before graduation, and eventually moved to Brooklyn, N.Y., where he worked as a salesman for the Oxford Button Co.

It was while he was in Brooklyn that he received his draft notice to go to Korea, where U.S. forces were working with United Nations troops to defend South Korea against an invasion from North Korea, which was supported then by China.

“I never thought I would be drafted,” Shiner said. Like many youths, he felt he was safe from war and adversity.

He also didn’t understand what the U.S. was doing in Korea because war had not officially been declared. “I didn’t think they had a right to draft anybody.”

After receiving his assignment at Fort Devens, Mass., Shiner shipped off to Camp Polk, La., for training as a tank loader. His siblings — sisters Elizabeth, Helen and Bernice, and his brother, Edward — were living nearby at the time, and after being at the camp for two months, he received a 72-hour leave to visit them.

It was then he made his first mistake.

“I extended my leave two days,” he said. “When I came back the lieutenant had me confined to the company area for 30 days. He was not happy with me.”

Shiner accepted his punishment, but once he fulfilled it, he jockeyed for another 72-hour leave to visit his fiancee and family in New York.

“I extended my leave, this time by three days.” But while in New York, he was at a restaurant and heard a television report commanding all personnel from his division to get back to camp immediately.

“Then I knew we were going overseas to Korea. I called the lieutenant up at Camp Polk, and told him what I’d seen on TV. He said, ‘Whatever you do, Shiner, do not get into trouble with any police. Do not get picked up by any military. Get back to camp immediately.’”

That was his second strike.

Shiner returned to Camp Polk to get his shots and final orders to go overseas. He sailed to Korea from San Francisco for more training on Japan’s Hokkaido Island.

The sea journey took 28 days and the whole time Shiner was assigned to kitchen duties. “No movies, no type of excitement for me. But remain down there and clean your weapons, shine your shoes. If the kitchen needs you for kitchen duty, you’re available.”

After training on Hokkaido, Shiner and the troops went to Inchon, to replace the 1st Cavalry Division. They took a position on the front line, just south of the 38th Parallel, which formed the border between North and South Korea. American troops were placed just below the parallel to defend South Korea from incursions by enemies in the north.

Three weeks into his stay in Korea, Shiner went to his commanding officer, Capt. John W. Russell of the 279th Heavy Tank Company, and apologized for his earlier misbehavior. “I told him I had seen the light. … I realized I had done something wrong. Who am I to take on the government and say the government is wrong?”

Russell told Shiner that he could redeem himself if he worked hard.

“In the tank, I started out as a loader, which was a private. Then I became the driver, and that is a corporal. And that was within a month. I became a soldier. I’m telling you, I did. I volunteered for everything. I wanted to be on the good side. I knew I did wrong.”

He then was promoted to sergeant and became tank gunner for the 60-caliber machine gun. After three months, he became tank commander and sergeant first class. As commander, he was in charge of all tank personnel and equipment.

From his position near the 38th Parallel, Shiner and his tank crew witnessed the rather constant air battle between the two sides. They bombed the enemy, which was dug deep into the hills, just north of the parallel.

The enemy struck back especially when his unit would reposition the tanks along the line in the evening. “They seemed to know when it was five or six in the evening. … They threw the artillery in.”

The weather was often uncooperative. Once his unit got caught around Pork Chop Hill during monsoon season. And there was severe cold known as “dry winter,” Shiner said. “If you didn’t have your gloves on and you touched the tank with your bare hand, you would leave your skin right on the tank due to the dry snow and ice.”

By late summer of 1952, many in Shiner’s outfit headed home. But he had to remain behind another month to make up for past transgressions. “I knew they were right in what they were doing, but I wanted to go home.”

During this time, he had a bad scare on the battlefield. He and his crew were sent to the front line to defend a special mission just north of Seoul. As it turned out, Shiner’s tank was not needed in the mission but it ran into trouble when it headed back to camp.

“By turning the tank, to get it into a position to go forward, we picked up some barbed wire in the track. The engineers cut loose the wire — luckily they were there — and we got out of there without setting off any flares. That would just light everything up.”

“I said to myself, ‘if I (hadn’t been) AWOL, I would be home right now. Here I am, cutting this barbed wire off the track. In the meantime, the enemy artillery was just pounding our area but we got out of there safely without any injuries or casualties.”

The month passed and he finally got word he could go home.

“I was so happy. They had some beer there and I was so happy I had a few beers.” But then came news he wasn’t expecting.

“Believe it or not, I was asked — and I’m not lying to you — they said, ‘Sergeant, we would like you to sign up for two more years and get a field promotion.’ He couldn’t believe that after his shaky start, the Army would want him to stay. “My response was, ‘I thank you. I’m going home to get married and go to Indiana.’”

Yet another surprise was in store as Shiner boarded the ship for home.

“We were boarding ship, to go to the States, and as we were going up the plank, they said to me, ‘Sergeant, don’t make a right, make a left.’ And I said why am I going left when all the other troops are going right?”

“They said, ‘You’re going to a cabin.’ They gave me a cabin. All that I put them through, they gave me a cabin to go home.”

Shiner’s trip back home did not go entirely as expected, however.

He was in charge of about 15 soldiers headed to Fort Dix, N.J. They flew from San Francisco to Philadelphia, and then caught a bus to Fort Dix. The bus went by the home of one of the men, who begged Shiner to ask the driver to stop for a few minutes so he could see his parents.

At first, Shiner refused but then he relented because he knew that all the soldiers, himself included, had seen some ugly times.

“I said to myself, ‘I got to be nice to this boy. Let him see his mom and dad.’ It will only take a half an hour, 15 minutes, and we’ll be on our way.”

But there was a wedding in the neighborhood and the short stop turned into four hours. The bus rolled into Fort Dix late, and the welcome guard there was not pleased. The guard warned Shiner he could be in trouble.

“Trouble is my middle name,” Shiner replied.

He finally returned to New York, hoping to marry his fiancee and bring her back to Indiana.

“Before I gave her the ring, I told her, ‘Remember we are moving to Indiana, Pa., due to the fact that it is the only town that I know that has a Capitol Restaurant, a Dairy Dell and Hess’s Restaurant. It is a beautiful town and that’s where we are going to live.”

But he couldn’t quite convince her to move from New York to Indiana. Their engagement ended and Shiner returned to Indiana alone. He eventually found work in several sales positions and spent 26 years at Penn Furniture in downtown Indiana.

“I love selling. I love talking to people.”

He found other loves as well. He and his wife, Shirlee, have been married for 58 years and have two daughters, Cindy Haldin and Rhonda Stefanik, both of Indiana, and a son, Edward Shiner, of Greensburg, from his first marriage. He also had another son, the late Hank Jr., and has four grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Besides work and family, he found time to be a proud member of the Indiana American Legion Post 141 for the past 50 years, cheer on the New York Mets and go about town with his poodle, Tuffy. “He goes with me all over. They all know Tuffy.”

All of this in his beloved Indiana, his favorite place in the world. “I came to live where I wanted to. My wish came true.”

View more photo galleries by Post 141 in Indiana, Pennsylvania